- Joined

- Nov 3, 2022

- Messages

- 141 (0.22/day)

| System Name | Every cuss word I can think of, and a few more I've made up |

|---|---|

| Processor | Ryzen R9 5900X |

| Motherboard | Asus Tuf B550-PLUS |

| Cooling | Scythe Mugen 5 Black Edition, Corsair Commander Core XT with six LL120s |

| Memory | 2x16 DDR4-3200 Patriot Viper 4 Blackout PV432G320C6K |

| Video Card(s) | Asus KO-RTX3060ti-8GB-OC |

| Storage | 1TB WD Blue SN570 PCIe3 M.2, 8TB WD Black 8TB HDD, Pioneer BDR-212DBK |

| Display(s) | 75" Hisense A6, 23" Dell ST2310 |

| Case | Fractal Pop XL Air, black on black |

| Audio Device(s) | Realtek Onboard Audio, Digitech RP-250, Yamaha DGX-205 |

| Power Supply | Corsair RM850x |

| Mouse | Logitech K520 |

| Keyboard | Logitech K520 |

| Software | LibreOffice, BeamNG.drive, Classic Doom and variants, ATS, NCH VideoPad, OBS Studio, MPC-HC, iCUE |

| Benchmark Scores | CB R23: Multi-Core 21539 - Single Core 1592 *PBO Auto, GPU no OC, room for improvement?* |

I've noticed there seem to be some rather ridiculous and utter myths and misinformation regarding cooling, particularly air cooling. First and foremost, a popular tech YouTuber did a comparison video testing various air and liquid cooler performance, concluding that while liquid cooling did deliver more consistent temperatures, they were only SLIGHTLY lower – 5C or less, and that air coolers performed quite comparably when properly sized and set up. They made a statement in that video – that liquid cooling was cool if you like to spend more time tinkering with your PC as opposed to using it. To me, that pretty much says it all, as a difference of less than 5 degrees in temp is more or less identical.

NOTE: If you’re planning a simple budget build with less than eight cores and entry-level graphics and other hardware, you won’t need a ton of cooling – in fact, stock air coolers should be just fine in most cases. However, if your build is a stepping stone to bigger and better later on, it makes sense to pave the way for this in choosing components with better cooling in mind for any future upgrade. Otherwise, you’re spending more money in the long run.

My 5900X build's cooling system uses an iCUE Commander with six 120mm fans, and the Scythe Mugen 5 which uses a 120mm fan, seven in total, but they don’t even run that hard below 70C. As illustrated in the screenshots below, CPU Package temperature idles in the 38C-42C range. Under light to moderate use, it hovers around 48-58C, sometimes as high as 63C. Cinebench R23 is the stress test to end all stress tests as far as I’m concerned. And even with a 30-minute CB R23 loop, temp peaks at 75-76C. Post-test recovery to idle temp range takes around 45-90 seconds. So it cools quite well, and at just 34 square inches of intake area for cooling, my Corsair 4000X case is hardly the best-ventilated case on the market -- the 4000D Airflow would do even better, although the 4000X has air filters where the D does not.

My build was hardly a typical process or timeline, but I admit that in the planning stage for my build, I was skeptical of air-cooling and thought the 5900X needed liquid cooling, but others convinced me that a properly set up air cooler is plenty for even the most robust builds, and more reliable than liquid cooling. However, component selection and initial set-up are a bit more critical. As no one else seems to have done so, I thought I'd explain a few myths and misconceptions, as well as share some insight on component selection and tips for proper setup of an air-cooling system.

MYTH #1 – “My processor requires liquid cooling”

This simply is not true in 99.99% of cases. While it is true that more cores and more threads = more heat, my recent R9-5900X build is proof that air-cooling is more than sufficient for consumer market applications. This is not meant to bash those who like liquid cooling, but VERY little, if anything, on the consumer market actually requires liquid cooling. Also, I feel it often is a band-aid for poor component selection and / or an off-the-shelf answer for those who don’t understand how to properly set up air cooling, or the dynamics of cooling.

MYTH #2 – “Air coolers are junk. They don’t work”

This is not true, either. Air coolers do take a bit more care in component selection and time in initial setup. But properly set up, they are actually more reliable than liquid cooling in most, if not all cases. However, certain factors determine whether a particular cooler is suited to your needs. A poorly-ventilated case can actually insulate the components, making your system a furnace even the best cooling system can’t tame. Conservatively speaking, poorly-ventilated cases hamper cooling by as much as 30-50%, and that’s not the cooler’s fault. For example, you simply cannot stuff a 360mm AIO into an NZXT H510 and expect it to cool. It simply will not be able to get air to do so, because the front is solid steel and your radiator is blocking your airflow. Common sense.

Cooling requires three things – heat transfer, ventilation, and airflow. Hotter processors need bigger coolers, because a cooler’s surface area determines heat transfer ability. Too little surface area substantially hinders cooling. Think of it this way – if you were to cut a Mugen 5’s heat sink into three equally sized sections top to bottom and lay them end-to-end, its surface area is quite comparable to a liquid-cooled radiator. Air coolers simply stack their surface area, where liquid radiators spread it out. Some also use two fans, as opposed to one, which can make a difference.

Another pair of factors apply to the larger, higher-performance air coolers as well. The impact of heat sink size has already been explained. However, what’s underneath impacts cooling capacity as well, and I don’t mean the processor. First, some have more heat transfer tubes than others. For example, the Scythe Mugen 5 has six heat tubes transferring CPU plate heat to the heat sink. Most, if not all Noctua offerings, such as the NH-U12A, have seven, others can have as few as three or four. And this directly impacts cooling capacity, as to a point, more tubes = better cooling.

That being said, it MUST be made for your processor and suited to your setup. My 12-core 5900X cools quite well with the six-tube Mugen 5, so while it may not be an official formula or manufacturer’s recommendation, it makes sense to theorize that air coolers need one tube for each pair of processor cores. And I think this is the biggest factor in misconceptions about air-cooling, that those having issues with air-cooling are simply not selecting the right cooler for their needs.

But there’s another factor to look at here, as shown below. This is one area where airflow comes into play. The right-side cooler has six heat transfer tubes, compared to the left-side cooler’s four. In addition, the right-side cooler’s tubes are also perfectly round throughout the cooling circuit. The left-side cooler’s tubes flatten / taper sharply at the CPU plate, reducing their diameter. This is a bottleneck and also impacts cooling capacity. No pipe (or tube in this case) can flow more than its smallest diameter.

So, as you can see, a PC system’s cooling and performance both come down to component selection. Case selection has a bigger impact on this than you might think. There’s nothing wrong with a case that uses tempered glass / acrylic panels, but be sure it either provides some sort of air gap around the nose or side for air intake, as well as ventilation to the top.

System board choice can impact cooling as well. Many don’t know that boards have a voltage regulator module (VRM) that controls voltage to the processor. This effectively controls clock speed, but also has an impact on temperature as well. And cooling the VRM is critical with processors with higher clock speeds and core/thread counts. This is easy to determine. Some boards have no heat sink near the processor socket. Others may have one or two, some have larger ones than others. Bigger is better in this situation, especially with processors known for running hotter.

Something to note about fan choice. Quieter fans may not perform as well as others, but you’re not stuck with airplane noise, if you’re willing to put a little work into a custom fan control profile, which I’ll get to shortly. And with a well-designed and well-ventilated case (open grill front such as the Corsair 4000D Airflow), three 120s can flow more than two 140s. My setup has three 120s pulling in at the nose, two exhausting topside, one exhausting to the rear, and one blowing across the cooler heat sink.

MYTH #3 – “Air coolers aren’t cost effective”

MAJORLY not true. Most budget / entry-level builders can find air-coolers to serve their initial needs for under $30-$50, depending on their CPU choice. Even the best ones are cheaper than a liquid cooling setup. Noctua’s NH-D15 averages $100-$110 USD. The Scythe Mugen 5 cools quite well and at an average of $50-$60 USD, I think it is hands-down the best bang for the buck for CPUs over eight-cores.

EASY SETUP OF AN AIR COOLING SYSTEM

First, use the proper thermal paste, and properly apply it. Too little won’t cool well and too much will spill onto the board and other components, potentially damaging them. You don’t need a lot, just a thin coating on the processor lid (two or three dots on the lid center are usually sufficient), and take care to wipe any excess squeezing out over the lid edges as the cooler is tightened down.

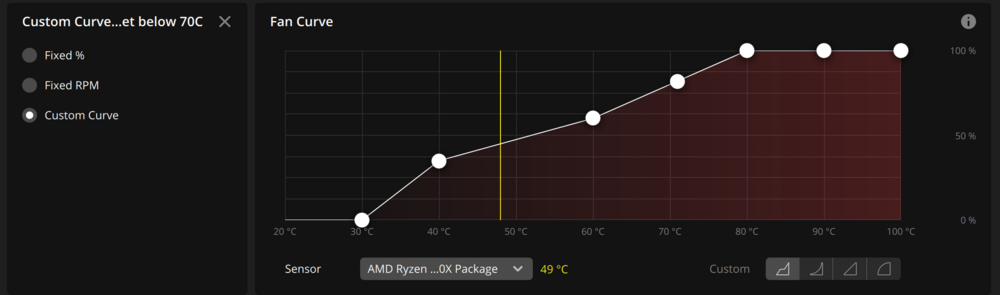

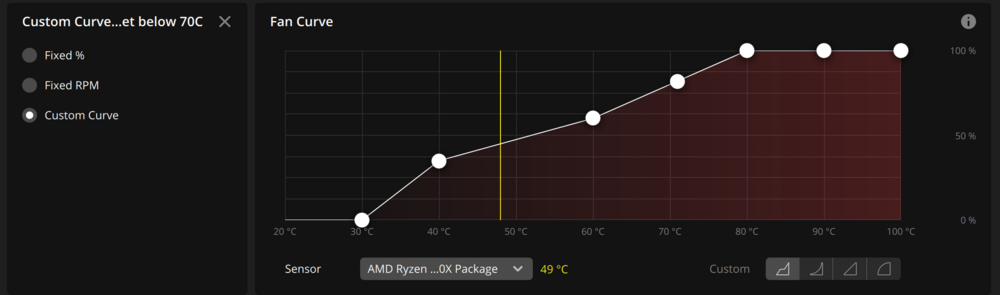

Tuning your case fan control curve is key. Most don’t like the airplane noise of constantly wide-open fans. Good news – it’s not necessary anyway. In a well configured cooling system, the fans generally need not exceed 70-85% capacity, as the upcoming screenshot of my fan curve shows. Also, the more options your fan controller software has, the better this will work. I use iCUE, which has adjustable settings to lock the fans at fixed percentages and RPM, as well as a custom fan curve, such as the one I use, shown below. Note that one size does not necessarily fit all when it comes to fan control curves.

Step 1: Most fan controllers can be set to a certain RPM and / or percentage of total output. Most fans max out around 900-1400 rpm, some at 1600. With the system idling (only your fan control software running), set all fans wide open for five minutes to get your lowest temperature. I know this will be annoying to listen to initially, but it is necessary to find the coolest temp your system can run. If you’re not seeing low 40s Celsius or better here, something is hindering cooling performance – my 5900X idles at 38C-42C.

Step 2: Every 1-2 minutes, dial your fans down 5%, or 100-250 RPM. Keep doing this until the temp starts rising, then dial the fans back up another 5% or 100-250 rpm to regain your lowest temperature. At this point, note your lowest temperature and fan RPM or percentage setting necessary to maintain it.

Step 3: If you don’t have it, download and install Cinebench R23.

Step 4: Set your fan control to wide open again.

Step 5: Set Cinebench R23 options for a 30-minute multi-core test, then start, minimizing the Cinebench window and switching to your fan control.

Step 6: Watch your CPU Package temp until it stops rising. If all is well, it should top out around 85% of max safe temp. NOTE: If it rises beyond 90-95% of max safe temperature for longer than 30 seconds, abort Cinebench and check to see that all fans are running and blowing the correct direction. Fans can create a deadlock of airflow when positioned and running against each other.

Step 7: Noting your highest stable temperature reading, repeat Step 2, noting the percentage / RPM setting necessary to maintain your recorded stable peak temp. When this has been determined, you can terminate the test.

Step 8: Open your fan controller software’s custom fan curve settings. Most will show dots on a graph, marked as fan percentage / RPM vertically, temperature setpoints horizontally. Each dot represents a setpoint.

Step 9: If silence is preferred, set your first setpoint at zero percentage or RPM just below or at your lowest temperature. Set your second setpoint by your lowest temperature and corresponding fan percentage / RPM setting. (Example: 0% below 30C, 20% at 30C)

Step 10: Find your fourth, fifth or sixth setpoint. Set it to your highest temp and fan percentage / RPM setting.

Step 11: The hard part is now over. The other setpoints between your high and low can now be tweaked to find a balance between stable temperatures and noise level.

NOTE: If you’re planning a simple budget build with less than eight cores and entry-level graphics and other hardware, you won’t need a ton of cooling – in fact, stock air coolers should be just fine in most cases. However, if your build is a stepping stone to bigger and better later on, it makes sense to pave the way for this in choosing components with better cooling in mind for any future upgrade. Otherwise, you’re spending more money in the long run.

My 5900X build's cooling system uses an iCUE Commander with six 120mm fans, and the Scythe Mugen 5 which uses a 120mm fan, seven in total, but they don’t even run that hard below 70C. As illustrated in the screenshots below, CPU Package temperature idles in the 38C-42C range. Under light to moderate use, it hovers around 48-58C, sometimes as high as 63C. Cinebench R23 is the stress test to end all stress tests as far as I’m concerned. And even with a 30-minute CB R23 loop, temp peaks at 75-76C. Post-test recovery to idle temp range takes around 45-90 seconds. So it cools quite well, and at just 34 square inches of intake area for cooling, my Corsair 4000X case is hardly the best-ventilated case on the market -- the 4000D Airflow would do even better, although the 4000X has air filters where the D does not.

My build was hardly a typical process or timeline, but I admit that in the planning stage for my build, I was skeptical of air-cooling and thought the 5900X needed liquid cooling, but others convinced me that a properly set up air cooler is plenty for even the most robust builds, and more reliable than liquid cooling. However, component selection and initial set-up are a bit more critical. As no one else seems to have done so, I thought I'd explain a few myths and misconceptions, as well as share some insight on component selection and tips for proper setup of an air-cooling system.

MYTH #1 – “My processor requires liquid cooling”

This simply is not true in 99.99% of cases. While it is true that more cores and more threads = more heat, my recent R9-5900X build is proof that air-cooling is more than sufficient for consumer market applications. This is not meant to bash those who like liquid cooling, but VERY little, if anything, on the consumer market actually requires liquid cooling. Also, I feel it often is a band-aid for poor component selection and / or an off-the-shelf answer for those who don’t understand how to properly set up air cooling, or the dynamics of cooling.

MYTH #2 – “Air coolers are junk. They don’t work”

This is not true, either. Air coolers do take a bit more care in component selection and time in initial setup. But properly set up, they are actually more reliable than liquid cooling in most, if not all cases. However, certain factors determine whether a particular cooler is suited to your needs. A poorly-ventilated case can actually insulate the components, making your system a furnace even the best cooling system can’t tame. Conservatively speaking, poorly-ventilated cases hamper cooling by as much as 30-50%, and that’s not the cooler’s fault. For example, you simply cannot stuff a 360mm AIO into an NZXT H510 and expect it to cool. It simply will not be able to get air to do so, because the front is solid steel and your radiator is blocking your airflow. Common sense.

Cooling requires three things – heat transfer, ventilation, and airflow. Hotter processors need bigger coolers, because a cooler’s surface area determines heat transfer ability. Too little surface area substantially hinders cooling. Think of it this way – if you were to cut a Mugen 5’s heat sink into three equally sized sections top to bottom and lay them end-to-end, its surface area is quite comparable to a liquid-cooled radiator. Air coolers simply stack their surface area, where liquid radiators spread it out. Some also use two fans, as opposed to one, which can make a difference.

Another pair of factors apply to the larger, higher-performance air coolers as well. The impact of heat sink size has already been explained. However, what’s underneath impacts cooling capacity as well, and I don’t mean the processor. First, some have more heat transfer tubes than others. For example, the Scythe Mugen 5 has six heat tubes transferring CPU plate heat to the heat sink. Most, if not all Noctua offerings, such as the NH-U12A, have seven, others can have as few as three or four. And this directly impacts cooling capacity, as to a point, more tubes = better cooling.

That being said, it MUST be made for your processor and suited to your setup. My 12-core 5900X cools quite well with the six-tube Mugen 5, so while it may not be an official formula or manufacturer’s recommendation, it makes sense to theorize that air coolers need one tube for each pair of processor cores. And I think this is the biggest factor in misconceptions about air-cooling, that those having issues with air-cooling are simply not selecting the right cooler for their needs.

But there’s another factor to look at here, as shown below. This is one area where airflow comes into play. The right-side cooler has six heat transfer tubes, compared to the left-side cooler’s four. In addition, the right-side cooler’s tubes are also perfectly round throughout the cooling circuit. The left-side cooler’s tubes flatten / taper sharply at the CPU plate, reducing their diameter. This is a bottleneck and also impacts cooling capacity. No pipe (or tube in this case) can flow more than its smallest diameter.

So, as you can see, a PC system’s cooling and performance both come down to component selection. Case selection has a bigger impact on this than you might think. There’s nothing wrong with a case that uses tempered glass / acrylic panels, but be sure it either provides some sort of air gap around the nose or side for air intake, as well as ventilation to the top.

System board choice can impact cooling as well. Many don’t know that boards have a voltage regulator module (VRM) that controls voltage to the processor. This effectively controls clock speed, but also has an impact on temperature as well. And cooling the VRM is critical with processors with higher clock speeds and core/thread counts. This is easy to determine. Some boards have no heat sink near the processor socket. Others may have one or two, some have larger ones than others. Bigger is better in this situation, especially with processors known for running hotter.

Something to note about fan choice. Quieter fans may not perform as well as others, but you’re not stuck with airplane noise, if you’re willing to put a little work into a custom fan control profile, which I’ll get to shortly. And with a well-designed and well-ventilated case (open grill front such as the Corsair 4000D Airflow), three 120s can flow more than two 140s. My setup has three 120s pulling in at the nose, two exhausting topside, one exhausting to the rear, and one blowing across the cooler heat sink.

MYTH #3 – “Air coolers aren’t cost effective”

MAJORLY not true. Most budget / entry-level builders can find air-coolers to serve their initial needs for under $30-$50, depending on their CPU choice. Even the best ones are cheaper than a liquid cooling setup. Noctua’s NH-D15 averages $100-$110 USD. The Scythe Mugen 5 cools quite well and at an average of $50-$60 USD, I think it is hands-down the best bang for the buck for CPUs over eight-cores.

EASY SETUP OF AN AIR COOLING SYSTEM

First, use the proper thermal paste, and properly apply it. Too little won’t cool well and too much will spill onto the board and other components, potentially damaging them. You don’t need a lot, just a thin coating on the processor lid (two or three dots on the lid center are usually sufficient), and take care to wipe any excess squeezing out over the lid edges as the cooler is tightened down.

Tuning your case fan control curve is key. Most don’t like the airplane noise of constantly wide-open fans. Good news – it’s not necessary anyway. In a well configured cooling system, the fans generally need not exceed 70-85% capacity, as the upcoming screenshot of my fan curve shows. Also, the more options your fan controller software has, the better this will work. I use iCUE, which has adjustable settings to lock the fans at fixed percentages and RPM, as well as a custom fan curve, such as the one I use, shown below. Note that one size does not necessarily fit all when it comes to fan control curves.

Step 1: Most fan controllers can be set to a certain RPM and / or percentage of total output. Most fans max out around 900-1400 rpm, some at 1600. With the system idling (only your fan control software running), set all fans wide open for five minutes to get your lowest temperature. I know this will be annoying to listen to initially, but it is necessary to find the coolest temp your system can run. If you’re not seeing low 40s Celsius or better here, something is hindering cooling performance – my 5900X idles at 38C-42C.

Step 2: Every 1-2 minutes, dial your fans down 5%, or 100-250 RPM. Keep doing this until the temp starts rising, then dial the fans back up another 5% or 100-250 rpm to regain your lowest temperature. At this point, note your lowest temperature and fan RPM or percentage setting necessary to maintain it.

Step 3: If you don’t have it, download and install Cinebench R23.

Step 4: Set your fan control to wide open again.

Step 5: Set Cinebench R23 options for a 30-minute multi-core test, then start, minimizing the Cinebench window and switching to your fan control.

Step 6: Watch your CPU Package temp until it stops rising. If all is well, it should top out around 85% of max safe temp. NOTE: If it rises beyond 90-95% of max safe temperature for longer than 30 seconds, abort Cinebench and check to see that all fans are running and blowing the correct direction. Fans can create a deadlock of airflow when positioned and running against each other.

Step 7: Noting your highest stable temperature reading, repeat Step 2, noting the percentage / RPM setting necessary to maintain your recorded stable peak temp. When this has been determined, you can terminate the test.

Step 8: Open your fan controller software’s custom fan curve settings. Most will show dots on a graph, marked as fan percentage / RPM vertically, temperature setpoints horizontally. Each dot represents a setpoint.

Step 9: If silence is preferred, set your first setpoint at zero percentage or RPM just below or at your lowest temperature. Set your second setpoint by your lowest temperature and corresponding fan percentage / RPM setting. (Example: 0% below 30C, 20% at 30C)

Step 10: Find your fourth, fifth or sixth setpoint. Set it to your highest temp and fan percentage / RPM setting.

Step 11: The hard part is now over. The other setpoints between your high and low can now be tweaked to find a balance between stable temperatures and noise level.

Last edited:

) and the mods are really good.

) and the mods are really good.